Saarbrücken, Germany – As the scientific community celebrates the 400th anniversary of the first mechanical calculator, attention turns to its creator, Wilhelm Schickard (1592-1635), a polymath and contemporary of Kepler. While the German government commemorates Schickard with a 20-euro collector’s coin, few know he might have also been history’s first academic UFO investigator. By pushing for precise descriptions of what he termed “wondrous signs” in the sky, Schickard faced severe criticism and outrage from his peers.

Who Was Wilhelm Schickard?

Beyond teaching Hebrew at the University of Tübingen, Schickard immersed himself in astronomy. In 1623, he introduced the Astroscopium, a paper cone showcasing the night sky. His work, “Ephemeris Lunaris”, detailed a lunar orbit theory, enabling the most precise ephemerides—positions of moving astronomical objects—of his era. Pioneeringly, he pinpointed meteor trajectories from observations at multiple locations.

His innovative graphical methods, used for eclipse calculations and Copernican system computations, were popular among his contemporaries. Beyond his scholarly pursuits, Schickard was a talented mechanic, crafting many of his instruments. Johannes Kepler even dubbed him a “two-handed philosopher”. By 1623, he had built the aforementioned first mechanical calculator. This “calculating clock” could add and subtract six-digit numbers. To facilitate complex operations, such as multiplication and division, it incorporated Napier’s rods in cylindrical form, supporting multiplication on the calculator.

By 1631, he succeeded Michael Mästlin as Tübingen’s astronomy professor. As a staunch heliocentric system supporter, he frequently exchanged ideas (and likely friendship) with Kepler. He even crafted the first handheld planetarium, depicted in his 1631 portrait.

The Sighting

Having amassed years of astronomical observation and computation expertise, Schickard made a groundbreaking discovery on January 27, 1630. He witnessed an aerial phenomenon that today we might label a classic UFO sighting. The event grew increasingly bizarre over several hours, eventually transforming into one of those “wondrous signs” skeptically viewed by academic peers of the time. Determined to document this event scientifically and precisely, especially given he was an eyewitness, Schickard chronicled his observations.

Having amassed years of astronomical observation and computation expertise, Schickard made a groundbreaking discovery on January 27, 1630. He witnessed an aerial phenomenon that today we might label a classic UFO sighting. The event grew increasingly bizarre over several hours, eventually transforming into one of those “wondrous signs” skeptically viewed by academic peers of the time. Determined to document this event scientifically and precisely, especially given he was an eyewitness, Schickard chronicled his observations.

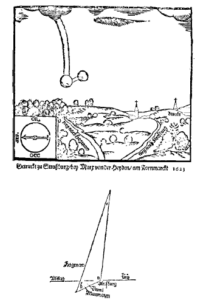

In his manuscript released two days later, titled “Description of the Wondrous Sign […],” he writes:

“While I was observing the stars on the clear sky as usual and turned my gaze from the southeast to the northwest, suddenly, a snow-white matter appeared, which I cannot rightly call a cloud since it was not flecked or frayed at the edges like a natural cloud but rather smooth and polished. Nor could it be called vapor, as it had a definite and elegant oval shape, whereas vapors flit about in irregular forms. This phenomenon was much brighter than any common cloud and was of a consistent and homogeneous nature.”

In summary, Schickard described witnessing a brightly lit oval or egg-shaped apparition in the northern sky, with a smooth, almost polished surface distinctly different from familiar clouds. Later, he narrates that two more white-hued phenomena joined this “white egg”, which he depicted in familiar terms of his era, resembling an “overturned kettle” and a “long, two-sided sharpened whetstone”. Unlike twinkling stars, these phenomena intermittently appeared and vanished, leaving Schickard uncertain whether they truly disappeared or simply hid from sight.

As the spectacle unfolded, diverse colored “lights or spots” joined the “egg”. This observation became one of the famed and notorious “sky battles”, where viewers believed they saw full-fledged aerial combats. In the subsequent part of his document, Schickard described an observation the following day of a “star during the day” which he couldn’t attribute to any known star, especially as it seemed to fly away “like a little bird”.

Recounting Schickard’s detailed account here would exceed this article’s scope. However, its unique quality stems from his deep-rooted astronomical and scientific background. Modern readers must decide: trust Schickard’s differentiation between known and otherworldly phenomena, or question the integrity of this otherwise meticulous but devoutly religious scientist in the more naive scientific context of his time? Regardless, parallels to contemporary UFO sightings are undeniable, from general descriptions of oval UFOs to the latest observations by US Navy pilots, who described such unidentified flying objects as “Tic-Tac“-shaped.