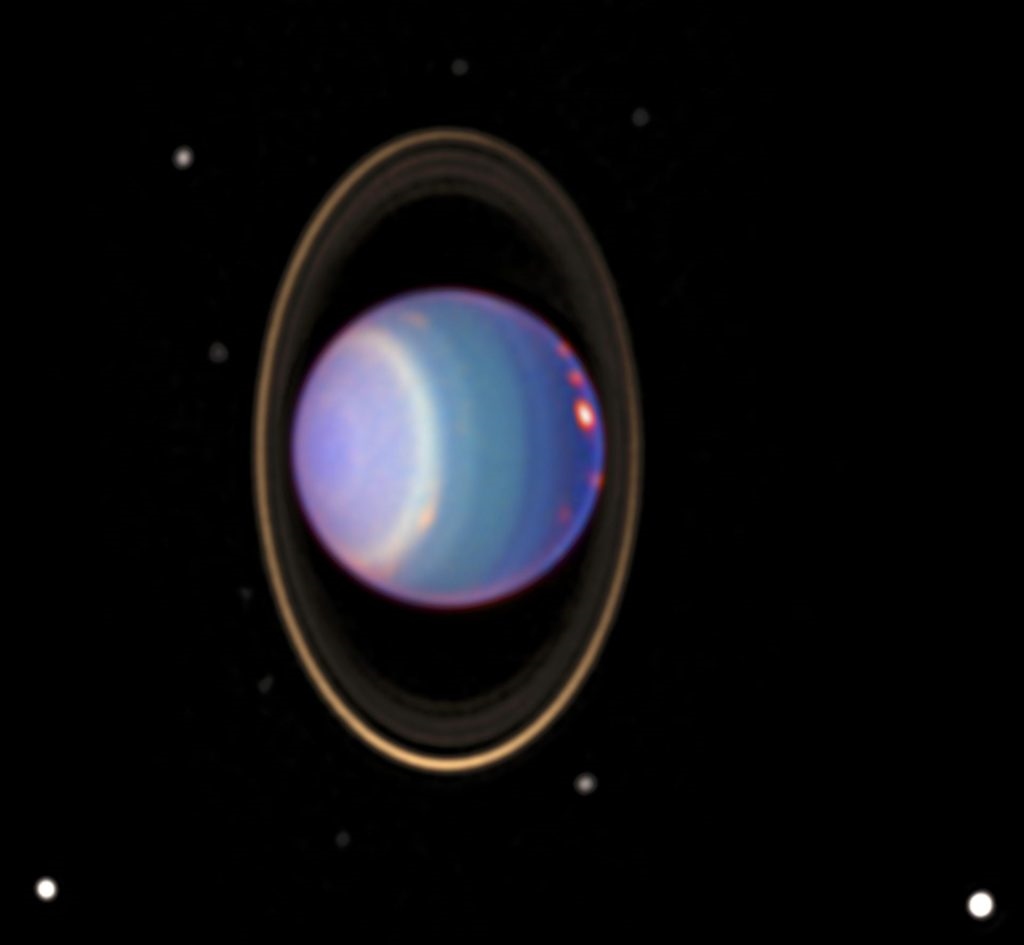

Laurel (USA) – 40-year-old radiation measurements from NASA’s Voyager 2 flyby suggest liquid oceans beneath the icy surfaces of two additional moons in our solar system. Ian Cohen’s team at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) reported at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in March, and in an upcoming issue of “Geophysical Research Letters,” that the Voyager data indicates two of Uranus’s 27 moons, Ariel and Miranda, are releasing material into space.

The data reveal that both moons are emitting plasma into space, though the exact mechanism behind this remains unknown. One intriguing possibility is that beneath their icy surfaces, the moons harbor liquid oceans and actively spew material from these oceans into space through geyser-like fountains.

Evidence of oceans beneath the ice crusts of Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus had previously been identified through particle and magnetic field measurements. Similarly, the old Voyager data now suggests the presence of such oceans beneath the icy surfaces of Miranda and Ariel.

“What’s interesting about these data is that the particles were confined to the immediate vicinity of Uranus’s magnetic equator,” Cohen explains. “Magnetic waves in the solar system usually propagate in latitudes. However, these particles were concentrated near the equator between the two moons.”

Scientists suspect that the particles originate from either Ariel or Miranda and come from a geyser fountain in the form of water vapor or from sputtering when high-energy particles strike the moon’s surface and knock other particles into space. “Currently, there’s a 50-50 chance that it’s one or the other,” Cohen elaborates.

However, so far, this is based on the data from a single observation of the region, with no further data available. “Until more measurements and data are available, there’s no way to accurately determine the source of these particles,” Cohen concludes.

Researchers have long suspected that the five largest Uranus moons, including Ariel and Miranda, possess hidden oceans after Voyager’s images of their surfaces revealed hints of geological exchange, including possible ice volcanoes.

In 2022, an expert panel of the US National Academies published a priority list for planetary science and astrobiology targets for the next decade. This list identifies the moons of the ice giant Uranus as the most important targets for exploration and the search for extraterrestrial life in the solar system.

The Voyager Mission

Launched by NASA in the late 1970s, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 have been nothing short of groundbreaking in the field of space exploration. The twin robotic probes, were designed to study the outer planets of our solar system and their moons, gathering invaluable data and insights that have shaped our understanding of these distant celestial bodies.

The two spacecraft were launched in 1977, with Voyager 2 taking flight on August 20th, followed by Voyager 1 on September 5th. Although Voyager 1 was launched later, its trajectory allowed it to reach Jupiter and Saturn before its twin. The original goal of the mission was to conduct close flybys of Jupiter and Saturn, studying their atmospheres, magnetic fields, and moons. Voyager 2 was also tasked with exploring the possibility of a flyby of Uranus and Neptune if the initial phase of the mission proved successful.

The two spacecraft were launched in 1977, with Voyager 2 taking flight on August 20th, followed by Voyager 1 on September 5th. Although Voyager 1 was launched later, its trajectory allowed it to reach Jupiter and Saturn before its twin. The original goal of the mission was to conduct close flybys of Jupiter and Saturn, studying their atmospheres, magnetic fields, and moons. Voyager 2 was also tasked with exploring the possibility of a flyby of Uranus and Neptune if the initial phase of the mission proved successful.

The Voyager missions exceeded all expectations, providing stunning images and data that vastly expanded our knowledge of the outer planets. The probes discovered new moons, active volcanoes on Jupiter’s moon Io, and intricate ring systems around the gas giants. Voyager 1’s famous “Pale Blue Dot” image, taken in 1990 from a distance of about 3.7 billion miles, provided a humbling perspective of Earth’s place in the cosmos.

Voyager 2’s extended mission allowed it to fly by Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989, making it the only spacecraft to have visited these planets. During these encounters, Voyager 2 revealed previously unknown details about Uranus’s atmosphere and magnetic field, as well as its system of rings and moons. The probe’s close encounter with Neptune provided important information about the planet’s atmosphere, magnetic field, and largest moon, Triton.

Both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are now on an interstellar mission, having crossed the heliopause – the boundary where the solar wind’s influence wanes and interstellar space begins – in 2012 and 2018, respectively. They continue to send back data about the environment beyond our solar system, providing invaluable insights into the nature of interstellar space.

The Voyager missions, with their rich history and numerous discoveries, have been instrumental in shaping our understanding of the outer planets and their moons. The data they collected, such as the recent findings suggesting the presence of liquid oceans beneath the icy surfaces of Uranus’s moons Ariel and Miranda, continue to fuel new research and discoveries even decades after their launch. These missions have not only expanded our knowledge of our own solar system but have also inspired generations of scientists and dreamers to continue exploring the cosmos.